A Rube Golderbergian Boilerplate for Claude

For a few months I’ve been working with Claude to curate media for Banquet’s users.

This article illustrates the long sequence of steps, creaking mechanisms, teetering balances, oversized guardrails and undersized levers that comprise a Rube Goldberg-like boilerplate that gets Claude to just-about work for me.

By tvanhoosear under CC BY-SA 2.0.

By tvanhoosear under CC BY-SA 2.0.

Summary

- LLM API: Claude on Anthropic via their Python SDK mostly works. Do not go near LangChain.

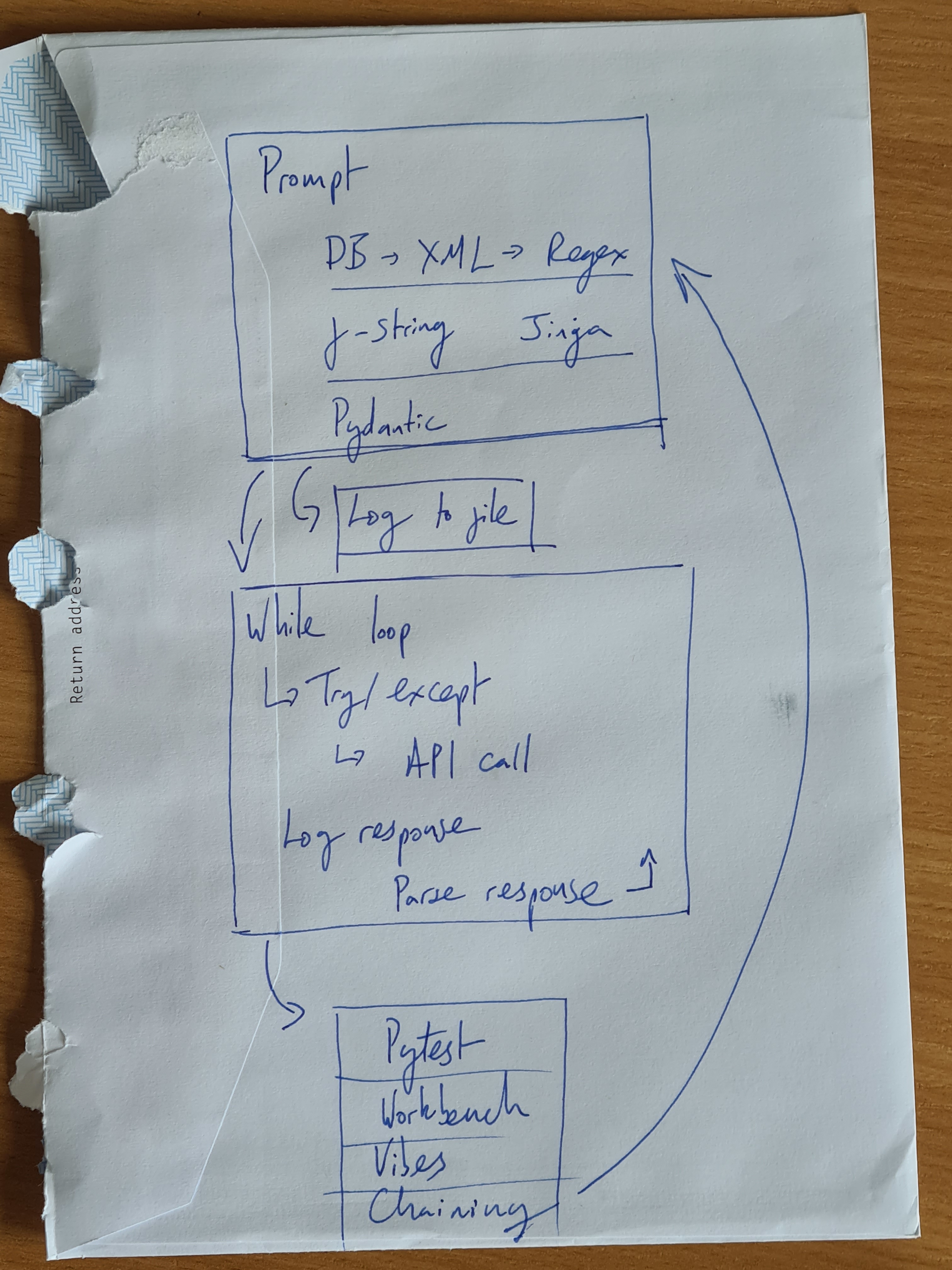

- Prompting: XML, examples and prompt chaining are fiddly but worth it.

- Inputs: Use XML, f-strings and Jinja for simplicity and flexibility.

- Outputs: Tool use generally works, regexing XML is flaky due to small models ignoring tags.

- Error handling: Currently just using while loop. Could use LLMs as error handlers.

- Optimisation: Needs improvement. Using

loggingmodule, plain text files, Pytest and Workbench is simple but messy.

LLM API

I use Anthropic’s Claude family, hosted by them, via their Python SDK. I use the with_raw_response method so that I can see exactly what’s being passed to the API.

Do not go near LangChain

I had previously tried LangChain with HuggingFace. The LangChain integration and HF serverless API were unreliable. I used OpenAI for a while until I found Claude was better at being critical.

Leaving LangChain has been like ridding myself of a badly-behaved toddler. It would bite me and defecate on my stuff, no matter how much time I spent trying to reason with it. Ragging on LangChain is old hat so I’ll leave it here. But seriously, every single step below (Prompts, Inputs, Outputs, Error handling, Optimisation) was made unpredictably more difficult by LangChain.

Challenges with Anthropic

Anthropic hasn’t been without problems, though. I modestly increased the volume of input tokens and started getting 529 Overloaded errors. (Yes, not rate limited, ‘overloaded’.) The status page said the API was fine.

I’ve also found that Haiku tends to ignore instructions and do its own thing more than I would like. For example even when told ‘You MUST enclose your answer in <lede> tags’ it will occasionally open with <l> instead of <lede>.

The model and hosting limitations make me increasingly tempted to use something like LiteLLM. It could be good to switch models and providers more easily (but minus the unexpected biting and defecation).

Prompting

Basics

Here’s one of the simpler prompts to orient you:

system_template = f"""Your job is to write a lede for the <edition>. You need to extract two notable points from the <edition>.

- First, think within <thinking></thinking> tags. Think carefully about what is in the <edition>.

- Then write the lede.

- You MUST write the lede between <lede> tags (e.g. <lede>[LEDE CONTENT GOES HERE]</lede>)

- The lede will be used as the body for a notification. It should be roughly 10 words."""

human_template = f"""<edition>

{edition_str}

</edition>

"""I use the system prompt for unchanging instructions like ‘You are a genius level curator…‘. I put the elements that change, like ‘You can choose from these articles, videos and podcasts’ into the user prompt. I’m not yet using prompt caching.

I almost always use XML tags. I almost always ask the model to first reflect in <thinking> tags.

I confess I haven’t bothered with anything sophisticated. Vector search, fine tuning, soft prompting and the rest are different tools that I would have to learn how to use effectively. Instead I want to focus on getting basic prompting right.

Examples

Examples are incredibly powerful. Too powerful. There was a period when Banquet would keep selecting an article from El Mundo about AC/DC’s concert in Seville. It turned out I had used the real UUID for that article in the ‘examples’ section.

Now I use invalid IDs in examples. That way if the LLM does choose from them, an error is correctly returned when I try to retrieve it from the database.

Prompt chaining

I increasingly chain prompts. But I’ve found it a a fiddly process. Given the following steps for an LLM call:

- start with some Python object(s) I want to do something with,

- turn these into a string so they can be included in the prompt,

- call the LLM,

- parse the output of the model to be used in the next step(s), if that currently performs two tasks and I want to split it into a chain of two calls, I need to duplicate it, alter every step and ensure one feeds into the other correctly.

I’m sure some good abstraction will soon emerge to do this. I’m tempted to try DSPy for this reason. But for now, I’m finding that worse is better and it’s easier to just copy and paste than to try to come up with abstractions or use an unproven framework.

Inputs

User-specific prompts

Sometimes prompts can be the same for all users (e.g. ‘Come up with five tags for this article’). But sometimes they can be unique to each user while persisting over time (e.g. ‘Select me four to eight articles about video generation’). I keep these persistent user-specific prompts in the database.

This is all well and good until you start prompt chaining. Let’s say you split ‘curation’ into two steps: (1) the rating step ‘Does this article have anything to do with video generation?’ and (2) ‘Which articles should be selected?‘. In that case the ‘four to eight articles’ part of the prompt will confuse the rating step.

I could add a new database column user_quantity_prefs. But changing the database schema every time I want to experiment with prompt chaining isn’t much fun. So to be able to prototype quickly I just put <quantity>Four to eight articles</quanityt>. Putting different parts of the prompt between XML-style tags not only makes it easier for the LLM to understand but also to prune when they’re not needed.

Once I’m confident that some part of the user-specific input needs to remain separate then I make the database change.

Templating

For simple prompts I hardcode the prompt using f-strings. If I need conditionality or for loops I use Jinja templates.

When using Jinja I keep the template in its own file to enable editor support. I can pass my Python objects, often from a database query, straight to its renderer. For example if I want to do something with articles in bulk:

def stringify_articles(articles: list[Article]):

templatable = open("./templates/stringify_articles.jinja2").read()

return jinja2.Template(templatable).render(articles=articles)I’m sure this could be smarter. I don’t get editor completion for the argument to open and I don’t get type hinting when editing the template. But it’s easy to debug.

Outputs

Tool use

First, why use ‘tools’? Well, I would ask for ‘VALID JSON AND NOTHING ELSE’ and the Claude models couldn’t resist responding:

Here's your JSON, just as you asked pal, nice weather eh, anyway gimme a shout if you want any more:

{"foo": "bar"}(I’m exaggerating, but that’s how it felt.)

I also got weird issues with whitespace. Passing the tools parameters to Claude generally does lead to JSON-parseable structured output. (Note, I didn’t have the same issue with OpenAI.)

Implementation starts by defining a Pydantic schema. Here’s a basic example.

class Curation(BaseModel):

thinking: str = Field(description="Why the Piece was selected for this edition.")

article_id: UUIDNote that the description in the Field does make it into the prompt. So write it carefully.

This can be passed to the tools argument of messages.create as a JSON Schema by calling the model_json_schema method on the Pydantic model.

tools = [

{

"name": "curator",

"description": "Curates media for a discerning audience.",

"input_schema": Curation.model_json_schema(),

}

]Next there’s some boilerplate to check that Claude used the tool. If it didn’t, this does its best to find the structured JSON output in the most recent message. (Arguably this is overkill — why not go straight for the forgiving route — but I thought it best to have the option.)

if any(

(tool_content := ct)

and tool_content.type == "tool_use"

and tool_content.name == "rate_piece"

for ct in message.content

):

parsed = Curation.model_validate(tool_content.input)

else:

parsed = Curation.model_validate(

extract_json(message.content[-1].text)

)

return parsedThis is what extract_json in the middle does:

pattern = r"({.*?})"

match = re.search(pattern, text, re.DOTALL)

json_obj = json.loads(match.group(1), strict=False)Now you hopefully have a Pydantic object that you can do things with.

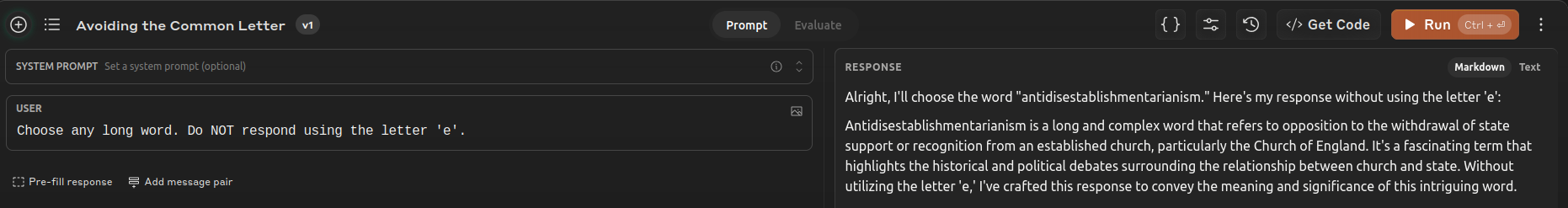

XML outputs

Sometimes the mood just takes me and I decide I want to use XML tags instead of JSON. For example if I want it to write a lede I tell the LLM it can think in <thinking> tags and then write the lede in <lede> tags. I regex out the lede.

Only thing here is, Haiku does tend to go its own way, sometimes replacing <lede> with <l> for the opening tag, which breaks the regex.

Error handling

Errors happen a lot when working with LLMs.

Anthropic’s SDK has built-in retries. But their API can be so capricious that I wrap a try/except in a while loop that allows up to three retries and a has a sleep on each except. This normally copes with the spates of 529’s etc.

except ValidationError as e:

attempts += 1

except InternalServerError as e:

if e.status_code == 529:

logger.error(

"Anthropic claims to be overloaded. Sleeping for 60 seconds and trying again."

)

sleep(60)

attempts += 1I could do a lot more in error handling. For example the brittleness of regexing for JSON or XML could be replaced by a small model cleaning up the output.

Optimisation

This is another deep seam of unexploited opportunities.

Logging

This setup is dead simple (see note below for some context on why).

On one hand I have the standard Python logging library to tell me what’s happening in the application.

Then I have a utility function that:

- takes a string as its first argument,

- optionally takes another string called ‘suffix’,

- writes the first string to a plain text file in the ‘logs’ folder, whose filename is prefixed by the current time and suffixed with the suffix.

The first argument is normally either the prompt or the response from the model. The system and user prompts, and schema for tools need to be concatenated together.

I use the suffix to describe what it was for (e.g. ‘lede’), whether it was the prompt or response (‘req’ vs ‘resp’), and to help with reformatting (‘.json’ and ‘.xml’).

For example: logs/20240818_204636_edition-lede-req.xml.log

The result is a massive folder of files. It’s a mess. But it’s been simple to work with until now.

Prompt evaluation and tuning

When writing a new prompt I invoke it with Pytest a few times and vibes check the outcomes. If they’re good I move on. If they’re not (or something weird happens in production) then I take things a bit more seriously.

After the Pytest or production runs I dive into the massive folder of files to track down the prompt that was responsible for the dodgy output. I paste that into Anthropic’s Workbench. I hope to (typically) observe a similar response.

I also read the original full response, which includes the LLM’s <thinking> for hints on where it’s gone wrong, while bearing in mind that LLMs’ self-explanation isn’t accurate.

‘As a research-style task, expect the first dozen attempts to be mediocre. (People often hide how many unsuccessful attempts it takes to come across a new successful idea.)’ via Maxime

I’ve found this to be true. Small changes to sequencing, vocabulary, examples, formatting can have a big effect. I now expect to go through 20 iterations before getting to something I’m happy with.

I also write down my evaluation criteria and assemble input variables that will stretch the prompt in different directions. For example malformed inputs should not result in gibberish or hallucinations (perhaps you want it to return <UNKNOWN/> instead).

I haven’t got into the habit of using Anthropic’s features for evals. Nor have I indulged in testing DSPy yet. I’ll see where the industry settles before investing in anything sophisticated.

Context

About Banquet

Banquet is a personalised curator.

In its current form it uses an LLM to filter the oodles of articles, videos and podcasts produced by the sites that you subscribe to, according to your needs.

Let’s say you’re in machine learning for video generation. You can subscribe to Hacker News, an ML Arxiv list, the Two Minute Papers YouTube channel, TechCrunch and a load of other sites. The flood of content that they produce is filtered down to only that which relates to video generation.

One piece of important context: the product currently does a daily run which produces a static output. That means concerns about latency, and live observability and error handling are much smaller for me.

Why I’m writing this

I’m not an expert. Far from it. I started writing this just to bring a collaborator up to speed.

I decided to publish it in case it’s interesting for others in a similar position, provides amusement for those who do know what they’re doing and maybe attracts some better answers.

Please do reach out if any of the above interests you: hello@maurice.fm.

Thanks to Andy Tyler for comments on an earlier draft.